At Primetals Technologies, we constantly strive to pioneer new and groundbreaking solutions for the steel industry. We work with passion, inspired by our close partnerships with steel producers from all around the world. Another source of inspiration are the great pioneers that have come before us—innovators who have made a profound impact on the way we live and changed the course of history. In this series, we look at the life, the challenges, and the achievements of some of the most outstanding pioneers of all time.

Amelia Earhart is perhaps best known as the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean and for her ill-fated attempt to circumnavigate the globe. Indeed, her disappearance—which still ranks as one of the great unsolved mysteries of the 20th century—tends to actually overshadow her enduring legacies as an aviation pioneer and role model. Her contributions to women’s equality have cemented her place as a historically significant figure both within and beyond the field of aviation. Not only did she break through the glass ceiling, she soared high above it.

Flying in the face of convention

Earhart’s pioneering spirit, love of adventure, and defiance of traditional gender roles was evident at an early age; she loved sports and the great outdoors, activities that went against the conservative and restrictive grain of the era in terms of attitudes towards women. A stunt-flying exhibition got her hooked on flying, and in 1920, Earhart and her father, Edwin, visited an airfield where Frank Hawks gave her a ten-dollar ride that would change her life: “By the time I had got two or three hundred feet off the ground, I knew I had to fly,” she exclaimed.

Earhart’s can-do attitude and fiercely independent nature were perhaps a product of her home life. She idolized her father, but his alcoholism taught her not to be reliant on men, while her mother Amy made a very bold move in relocating and taking her two daughters to Chicago. Earhart learned a crucial life lesson: how a woman could be the breadwinner, and that a woman’s life need not necessarily revolve around a man.

Throughout her childhood, Earhart remained unfaltering in her aspirations and kept a scrapbook of successful women in male-dominated fields, such as film direction, law, advertising, and engineering. Her high school yearbook from Chicago described her as “A.E.—the girl in brown who walks alone,” undoubtedly a result of her family’s frequent moves and being forced to switch high schools six times, which made it tough for Earhart to make friends.

With attitudes to women slowly beginning to change and the campaign for women’s suffrage gaining traction, Earhart impulsively dropped out of school during a trip to visit her sister in Toronto in 1917, feeling compelled to help with the war effort. She trained with the Red Cross as a nurse’s aid and remained until the end of the war. Here, Earhart would observe pilots in the Royal Flying Corps training at a local air field and an intense passion for aviation was fueled.

Amelia Earhart came perhaps before her time … the smiling, confident, capable, yet compassionate human being, is one of which we can all be proud.”

Walter J. Boyne

Aviation writer, retired US Air Force officer,

and former director of the National Air & Space

Museum of the Smithsonian Institution

After placing third in the 1929 Women’s Air Derby—the first transcontinental air race for women—, Earhart called a meeting of female pilots and the Ninety-Nines was founded.

The Ninety-Nines was set up as an association dedicated to the advancement of females in aviation, and its name was based on the number of charter members at the time. In 1930, she became the organization’s first president. The Ninety-Nines still exists today, representing women flyers from 44 countries, and is still dedicated to the advancement of aviation through education and scholarships. Earhart’s birthplace is now the Amelia Earhart Birthplace Museum and is also maintained by the Ninety-Nines.

Bitten by the aviation bug

Earhart survived the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 that hit Toronto, but was herself hospitalized with pneumonia and chronic sinusitis that later affected her flying. After the war, she enrolled at Columbia University as a pre-med student, but quit a year later. It was at this point, in 1920, that she took her life-changing ten-minute ride with pilot Frank Hawks.

Earhart threw herself into her new passion and began flying lessons in January 1921 with female flight instructor and pioneer aviator Neta Snook, the first woman to run her own aviation business and commercial airfield. To pay for lessons, Earhart worked various jobs; as a photographer, truck driver, and a filing clerk at the Los Angeles Telephone Company. Within just six months, she had saved enough to buy her own plane, paying $2,000 for a bright yellow second-hand Kinner Airster biplane that she nicknamed “The Canary,” in which she went on to set the first of many records by rising to an altitude of 14,000 feet. By December 1921, she had earned her National Aeronautics Association license.

Earhart’s big break

Following the buzz surrounding Charles Lindbergh’s solo Atlantic crossing in 1927, Earhart was invited to join an expedition that would make her the first woman to fly across the Atlantic—but only as a passenger. She accompanied pilot Wilmer Stultz and co-pilot Louis Gordon, and kept the flight log on a journey that took them from Newfoundland to South Wales in 20 hours and 40 minutes. Upon returning to American soil, a ticker-tape parade was thrown in New York in their honor, and a reception was held at the White House by President Calvin Coolidge.

Earhart’s newfound celebrity enabled her to finance her flying, and her career took off. She undertook a lecture tour, wrote a book, endorsed various products, and became one of the first celebrities to launch her own clothing line, featuring aviation-inspired details. Earhart was also appointed Aviation Editor at Cosmopolitan magazine, leveraging her position to popularize commercial air travel and, in particular, to campaign for the advancement of women in aviation. She published 16 articles, including “Shall You Let Your Daughter Fly?” and “Why Are Women Afraid to Fly?” In response to a letter sent in by a 13-year-old girl with ambitions of becoming a pilot, she said: “As far as a woman’s opportunities in flying go, I think they will improve as they have in all industries.”

- … that 10-year-old Amelia Earhart was left indifferent by her first sighting of a plane at the Iowa State Fair: “It was a thing of rusty wire and wood and looked not at all interesting,” she said. It wasn’t until 1920 that she took her first plane ride, and then only as a passenger.

- … that Amelia Earhart was one of the earliest supporters of the Equal Rights Amendment first proposed to Congress in 1923. She was also a member of the National Women’s Party, who campaigned for the right of women to vote.

- … that publisher George P. Putnam, whom she married in 1931, fed the nickname “Lucky Lindy” to the press because of Earhart’s likeness to aviator Charles B. Lindbergh. By all accounts it was a nickname that she despised.

- … that Amelia’s mother Amy was another record-setter, the first woman to ever climb Pikes Peak in Colorado. Amy encouraged her daughter’s passion for flying and used some of her inheritance to help pay for The Canary, Amelia’s first self-owned plane.

- … that Earhart struck up a friendship with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in 1932 and inspired her to sign up for flying lessons. Roosevelt did get her student permit, but took her plans no further.

A woman of many firsts

It was during the Atlantic crossing project that publisher George Putnam entered Earhart’s life. The two struck up a friendship that eventually led to marriage in 1931—after she agreed to his sixth proposal—, but even then, Earhart was keen to retain her independence; she believed in equal responsibilities and insisted on keeping her own name.

In the meantime, the pair began hatching a plan for Earhart to become the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic, and on May 20, 1932, Earhart left Newfoundland in a single-engine Lockheed Vega 5B, bound for Paris in a bid to emulate Charles Lindbergh’s flight from five years earlier. After 14 hours and 56 minutes, all the while battling strong winds, icy conditions, and mechanical problems, she landed in Culmore, Northern Ireland. It was an achievement that earned her the distinction of becoming the first woman to be awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross by Congress.

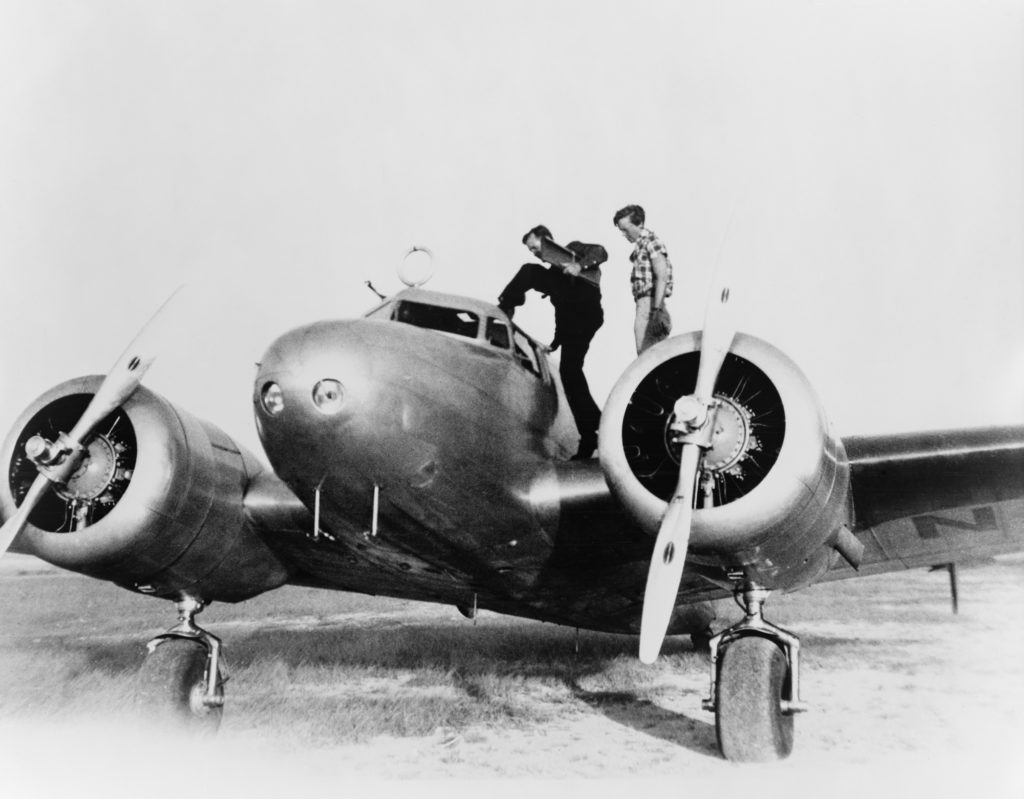

Earhart went on to set a succession of records, but had her sights set on the big one: becoming the first woman to fly around the world. A first attempt in March 1937, in a twin-engine Lockheed 10E Electra built by Lockheed to her specifications, ended in a crash after the forward landing gear collapsed, but did nothing to deter her spirits. She took off again in the rebuilt Electra on June 1, accompanied by navigator Fred Noonan, departing from Miami in an eastbound direction and following a roughly equatorial route.

Earhart and Noonan reached Lae, New Guinea, on June 29, having notched up 22,000 miles and with 7,000 still to go before reaching Oakland. On July 2, they set out for Howland Island, their next refueling stop, lost radio contact with the US coast guard cutter Itasca, anchored off the coast of Howland Island, and disappeared. President Franklin D. Roosevelt launched a two-week search, but on July 19, 1937, Earhart and Noonan were declared lost at sea. Had the pair completed that final flight, it would also have made Earhart the first to fly around the world at the equator.

There is no doubt that the mysterious circumstances surrounding Earhart’s disappearance have helped lift the aviatrix to legendary status, but she should be remembered for her courage, determination, pioneering spirit, and her achievements in advancing women’s rights. Earhart knew the risks, and in a letter to her husband—in hindsight written with unnerving clairvoyance—before her final flight, she wrote: “Please know I am quite aware of the hazards. I want to do it because I want to do it. Women must try to do things as men have tried. When they fail, their failure must be but a challenge to others.” Earhart always fought against the stereotypes, and although she did not consider herself a feminist, her story inspired a generation of female flyers, and is as valid today as it ever was as a motivational tale.

The US government spent $4 million on the search for Amelia Earhart in what was, at the time, the most expensive and extensive air and sea search in history. The crash-and-sink theory, the most popular one and the line held by the US government, suggests that Earhart and Noonan simply ran out of fuel before reaching Howland Island, crashing into and perishing in the Pacific Ocean. The theory put forward by the International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) speculates that they veered off course, landed 350 miles to the southwest on the then uninhabited Gardner Island (now Nikumaroro), and survived as castaways for up to several weeks. Conspiracy theories surrounding their disappearance claim that they were spies for the Roosevelt administration, returning to the United States and assuming new identities, or that they were captured and executed by the Japanese.

Timeline

1897

Amelia Mary Earhart is born in Atchison, Kansas, U.S.A.

1920

Earhart takes her first plane ride in California with famed World War I pilot Frank Hawks.

1921

Earhart begins flying lessons in January and passes her flight test in December.

1922

Earhart sets her first record, becoming the first woman to fly solo above 14,000 ft (4627 meters).

1931

Earhart sets a world altitude record of 18,415 feet (approx. 5613 meters) in a Pitcairn PCA-2 autogyro rotary-wing aircraft, the predecessor to the helecopter.

1932

Earhart becomes the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean, and only the second person after Charles Lindbergh.

1937

Earhart sets off on an ill-fated flight around the world on June 1, accompanied by navigator Fred Noonan.

1939

Earhart is declared legally dead on January 5.

1973

Earhart is inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

2006

Earhart is inducted into the California Hall of Fame.