This post is also available in: 简体中文 (Chinese (Simplified))

Dr. Toshiyuki Kajiwara (1928–2012) is known as the father of the pioneering 6-Hi mill with shiftable intermediate rolls. The Hyper UCM of Primetals Technologies is based on his mill design. In this interview, originally featured in Japan Metal Daily in 1990, we examine what inspired Dr. Kajiwara to create new solutions—and we hear about the steps he took that eventually led him to his 6-Hi innovation.

What got you interested in rolling mill development?

Dr. Toshiyuki Kajiwara: During college, I mainly studied thermal-engine technologies such as the gas turbine. But when I started my professional career, I was assigned to the rolling-mill division. Over time, I became deeply fascinated with the world of rolling mills, and it remained the area I worked in.

Where do you find inspiration for new inventions?

Kajiwara: I always find my inspiration on the work site. When I visit a steel plant, rather than meeting with executives, I go directly to the operators who actually handle the mills. I ask them how they run the mills, and see if they have any complaints about them.

What are the thoughts behind your inventions?

Kajiwara: Rolling mills belong to a group of machines that is somewhat closer to human beings compared to other types of machines such as engines. This is because their performance depends heavily on the expertise of the workers who operate them. It takes a skillful operator to unleash a mill’s full potential. This is the nature of rolling mills, and it is what inspired me to design a new mill, which would be easier to handle than any other mill in the world—a machine that operators would love. The mill I was going to create had to be the best mill in the world, not the second best.

How did you arrive at the creation of the 6-Hi mill?

Kajiwara: The story of the 6-Hi mill began when I visited a Japanese steel producer in the early 60s. Their site with a 4-Hi mill had a large inventory of rolls with a great number of different crown shapes, and the operators would have to select different rolls depending on the specification of each customer order. Changing rolls really was a lot of hard work. For the sake of the mill operators, I wanted to find a way to flexibly roll any pass schedule without having to exchange rolls.

And then you went on to invent the method of shifting the rolls to control the crown of the strip?

Kajiwara: Yes. You see, back in the day, it was thought that a larger backup-roll diameter was going to lead to less roll deflection. A method called work-roll bending was available to decrease deflection, but was not very effective. Deflection of backup rolls simply wasn’t the root cause of work roll deflection. Rather, the “undesirable contact area”—the area between the back-up roll and the work roll in the 4-Hi mill that extends beyond the width of the strip—was to blame. I found that the back-up rolls and the work rolls, even though they were made of hard steel, would deform by elastic force as if they were made out of rubber, as long as the undesirable contact area existed.

How then was your 6-Hi mill design different?

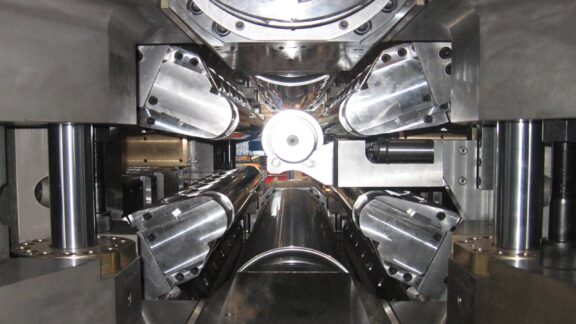

Kajiwara: My 6-Hi mill with no undesirable contact area made rolling more simple. It can roll strip of any width using straight work rolls, by flexibly shifting the intermediate rolls across their axes according to strip width. Not only that, the mill is capable of consistently delivering stable strip shape—even if the rolling force changes.

Has the 6-Hi mill evolved since its inception?

Kajiwara: New methods often face resistance, and so did the 6-Hi mill. We were asked many questions: Does it work in a large mill just as well as it does in a small mill? It’s fine for reversing mills, but how about for tandem mills? It works for cold rolling, does it for hot rolling? It can roll steel, what about aluminum? But every time we encountered a challenge, we overcame it—thanks to the passion of everyone involved.