Who are the great women in the world of steel? In this series, we ask them to step into the limelight. The steel industry may long have been a bit more on the conservative side, but this is changing fast. These days, it is only right that Metals Magazine reflect the global trend toward an even more diverse and powerful workforce in steel production.

Can you share with our readers a bit about your background?

Lucia Nares: My name has Libyan origins, but my entire family is from Mexico. I studied mechanical engineering at the University of Monterrey and began working at Ternium in January of 2012. Most of my work here has been in the hot-rolling area. When I started my career, at first I only knew that I wanted to be an engineer. I noticed that many students went in the same direction, which would have been materials. I wanted to be different, and this ultimately led me to automation and then to metallurgy.

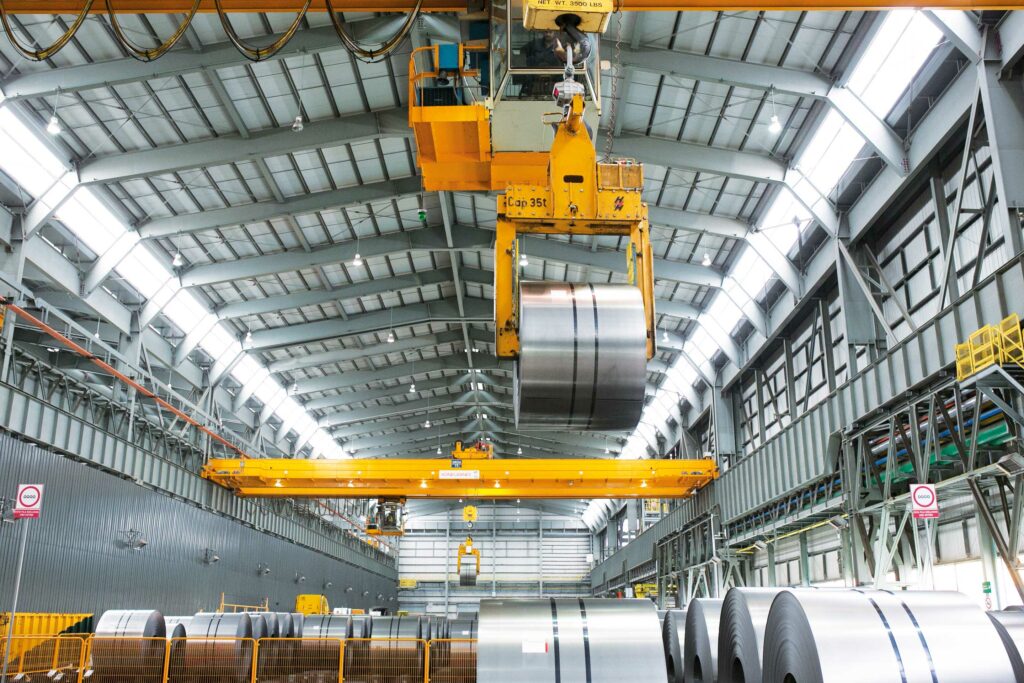

One of the projects Ternium has executed with Primetals Technologies involves a new hot-rolling mill. Is this investment enabling new possibilities in R&D?

Nares: The mill is a total game changer. We will be able to significantly extend the range of products we can manufacture. I feel we really needed a hot-rolling mill at this stage, and I’m very excited about the new possibilities it provides us with.

What role do automotive steels play in your larger R&D strategy?

Nares: It matters greatly to us. Automotive steels are at the center of the steel industry’s R&D work, and we always aim to develop lighter and harder materials for many car parts, for example wheels, structural components, and those relevant for increasing safety in the car.

When I started my career, many other students went into materials. I wanted to be different, and this ultimately led me to automation and then to metallurgy.”

Is it true that steels for the exterior of cars—automotive exposed—are the hardest to produce, and if so, why?

Nares: If cold-rolled material is used, I would say that it’s indeed relatively hard to make. But for producers of hot-rolled steel, it’s not quite so complex. With the new hot-rolling mill, we’ll be able to tackle the most challenging steels, as we’ve already got two galvanizing lines and a PLTCM. The new hot-rolling mill will allow us to establish a complete production chain on our Monterrey site.

Will automotive steels become less relevant once electric cars are more common?

Nares: No, not at all. Electric cars still require steel, even if they have to be lighter and despite the fact that electric cars use comparably less steel in terms of overall weight. There are even new parts that are necessary in the construction of electric cars, for instance, for protecting the battery. Carmakers have tried materials such as aluminum in the past, but they found that steel worked better for them in terms of stiffness, so they reverted to using steel again.

In your personal opinion, will hydrogen-powered cars soon succeed today’s electric cars?

Nares: I asked my husband about this, since he is a big car aficionado. It seems that hydrogen cars these days are still quite dangerous as the technology is not mature yet. So I would not expect to see hydrogen-powered cars become mainstream any time soon.

How long do your R&D projects take, for instance, the development of a new steel grade?

Nares: At least a year and a half. The definition of the material—the chemistry, the thermomechanical process, and the right cooling strategy—usually takes a few months. Aside from meeting the specification, the material will also have to satisfy our client, so we’ll align with them repeatedly in order to ensure they’ll be able to use our products for the intended applications. Once this is done, we can scale up production step-by-step.

What tends to be the most common challenge?

Nares: Ensuring that the material will work “in the field.” It has to be functional, in addition to meeting specifications.

Where do you draw inspiration from for new R&D ideas?

Nares: We get it from working with our clients. It is our job to make sure they’ll achieve their goals. This is what drives us.

I admire Galileo. He was both an innovator and an artist. If your work is ultimately results-oriented, it’s not always easy to infuse it with artistic beauty.”

Is there any innovator that you particularly admire?

Nares: I admire Galileo. He had a unique duality: he was both an innovator and an artist. If your work is ultimately results-oriented, it’s not always easy to infuse it with artistic beauty. Galileo achieved this.

What technology would you like to see invented, even if it probably never will be?

Nares: Producing drinkable water. I think that we might see shortages in the future. We should be more environmentally conscious, for ourselves but also for our children.

The Monterrey location plays a central role in Ternium’s larger company structure—this is where the headquarters is located, so most operational and strategic decisions are made in Mexico. Monterrey is not only responsible for orchestrating production centers in Argentina, Brazil, Guatemala, Colombia, and the U.S.A., but also excels in hot and cold rolling as well as product development. While Ternium is regarded as one of the world’s most relevant manufacturers of flat and long products, the Monterrey location has more recently been building a reputation as a highly dependable supplier to the automotive industry, which has grown dramatically in the region due to its proximity to the U.S.A.—its largest export market. Ternium is on a similar growth trajectory and plans to make substantial strategic investments over the coming years in terms of technology and even more sustainable processes, in order to strengthen its position.