At Primetals Technologies, we constantly strive to pioneer new and groundbreaking solutions for the steel industry. We work with passion, inspired by our close partnerships with steel producers from all around the world. Another source of inspiration are the great pioneers that have come before us—innovators who have made a profound impact on the way we live and changed the course of history. In this series, we look at the lives, the challenges, and the achievements of some of the most outstanding pioneers of all time.

Newton and gravity, Roentgen and X-rays, Mestral and Velcro, Plunkett, and Teflon; some of history’s defining scientific discoveries have been accidental, and fifteen-year-old James Watt’s incident with a kettle is no less momentous.

Young James is said to have sat at his aunt’s tea table for over an hour, watching the lid on a kettle rise and realizing the power of steam. Some dismiss the story as a myth, but James Watt went on to carry out many laboratory experiments using a kettle as a boiler to generate steam. His improvements to the steam engine sparked the Industrial Revolution, altered economies and laid the tracks for seismic social change.

The engine that drove a revolution

The young James Watt was described by his cousin, Marion Campbell, as a “sickly, delicate” but brilliant boy who would sit for hours poring over mathematical calculations and dismantling and reassembling his toys. James Watt’s talent for observation and practical application saw him become the engineering virtuoso behind the Industrial Revolution. His contributions to science and industry eventually led to the adoption of the unit of power named in his honor. Watt did not actually invent the steam engine, but it was his pioneering work on steam power that culminated in his invention of a separate condenser that significantly improved the efficiency of the Newcomen engine. This was arguably the most important invention of the 18th century, and his steam engine became known as “the workhorse of the Industrial Revolution.”

James Watt propelled us into the modern world, but it was his difficult early years and subsequent setbacks that defined him. The son of a shipwright and grandson of a noted mathematician, Watt was prone to bouts of ill health and was largely home-schooled by his well-educated mother, Agnes. At first, his father’s business prospered and grew, and the young James would make models and repair nautical instruments in the workshop. But during Watt’s teenage years, a series of commercial disasters struck and the business began to flounder. His father’s health began to fail, and two years after his mother’s death, 19-year-old James Watt was forced to move to London to study instrument-making. He mastered the craft in a single year.

An optimistic Watt returned to Glasgow in 1756, certain that as the only mathematical instrument-maker in Scotland he would have no problem finding work. His hopes were dashed by the Glasgow Guild of Hammermen, however, who blocked his employment because Watt had failed to put in the requisite seven years as an apprentice. So much for being a fast learner! It was a catch-22 for Watt: there was nobody for him to apprentice with, because there was no-one with his speciality. No-one said it was easy being a pioneer.

Raphael paints wisdom,

Handel sings it,

Phidias carves it,

Shakespeare writes it,

Wren builds it,

Columbus sails it,

Luther preaches it,

Washington arms it,

Watt mechanizes it.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Poet, philosopher, and essayist

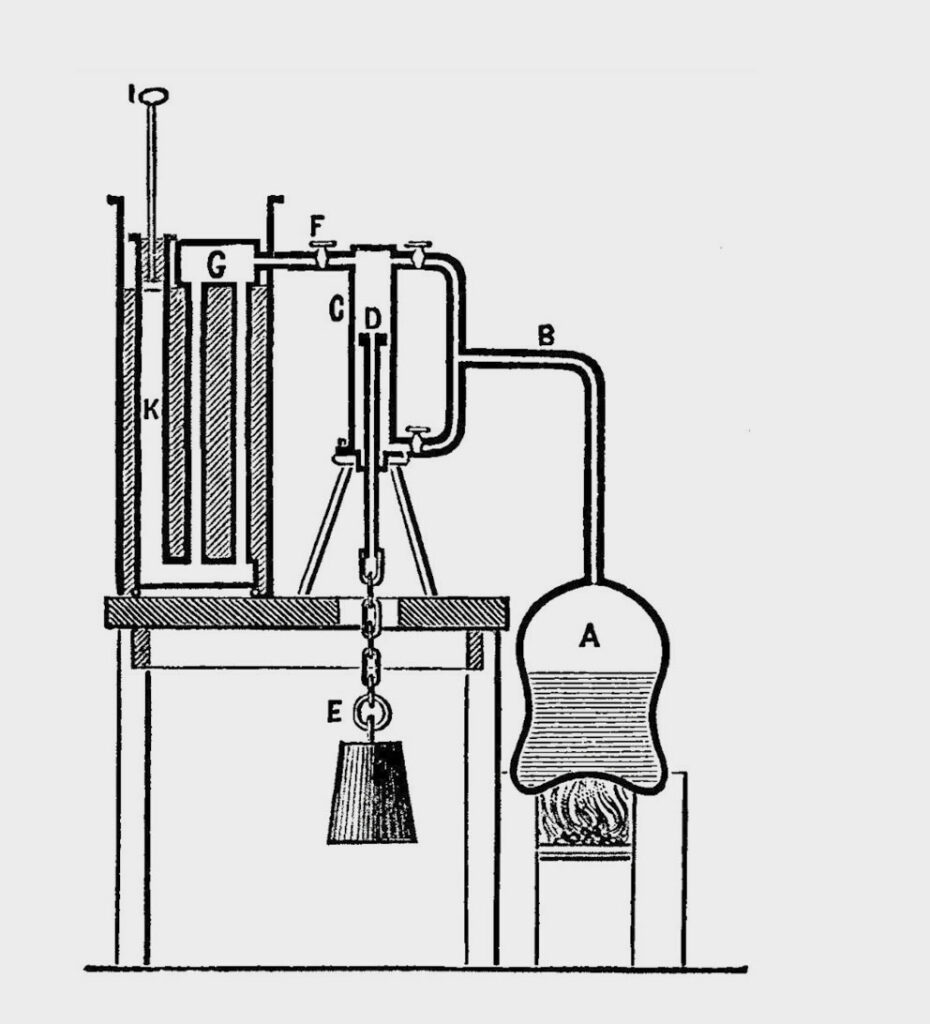

Newcomen engines were already in widespread use even before Watt’s birth, with the first working steam engine patented in 1698. When Watt was given a Newcomen engine to repair in about 1763, he was struck by its inefficiency. He came up with a design for a separate condensing chamber that addressed the Newcomen engine’s biggest shortcoming, its incredible waste of steam. The separate condenser was his first and arguably greatest invention, radically improving the power, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness of steam engines.

Revolutionary refinements

Watt was thrown a lifeline by the University of Glasgow, who employed him privately to restore a range of astronomical instruments. He was then given the opportunity to set up a small workshop within the university. Though lacking in business acumen, he entered into a partnership with architect and businessman John Craig, and over the next six years, they manufactured musical instruments and toys.

It was while working at the university that Watt became increasingly intrigued by the technology of steam engines. Adam Smith, the father of modern capitalism, introduced Watt to John Robinson in 1758, and Robinson in turn introduced Watt to the science of steam. The moment that altered the course of history came in 1763, when Watt was asked by the university to repair a steam-powered Newcomen steam engine, originally invented by English engineers Savery and Newcomen.

The Newcomen engine had already been widely used for decades to pump water out of mines, but is was very inefficient. Watt discovered that through repeatedly heating and cooling the cylinder, the engine wasted most of its thermal energy rather than converting it into mechanical energy. Watt’s solution was to use a separate chamber to condense steam without cooling the rest of the engine. His invention effectively turned a machine of limited use into one that would power the Industrial Revolution.

Since Watt was broke at the time, he was glad to be given another break by British inventor John Roebuck, who took two-thirds ownership of Watt’s invention. One major problem, however, was the lack of skilled labor needed to produce components with sufficient accuracy and precision. Meanwhile, the patent on Watt’s invention was proving hugely expensive, so to supplement his income, Watt was forced to work for eight years as a surveyor and civil engineer. Eventually, however, Roebuck went bankrupt and Matthew Boulton, owner of the Soho Manufactory near Birmingham, acquired the patent rights. Boulton finally provided Watt with access to the precision boring and instrument making he needed, and The Boulton & Watt Company was founded in Birmingham in 1774 to manufacture Watt’s improved steam engine. With demand high, the pair became leading figures in the Industrial Revolution, and their partnership continued successfully for the next twenty-five years.

The current U.K. £50 banknote, first issued in November 2011, features Matthew Boulton and James Watt and is itself an innovation; the Boulton and Watt note is the first Bank of England banknote to feature two portraits on the reverse, and is also the first introduced by the Bank to feature a green “motion thread.” According to the Bank of England: “The motion thread on the £50 note is woven into the paper. It has five windows along its length, which contain images of the £ symbol and the number 50. When you tilt the note from side to side, the images move up and down. When you tilt the note up and down, the images move from side to side and the number 50 and the £ symbol switch.”

Full steam ahead!

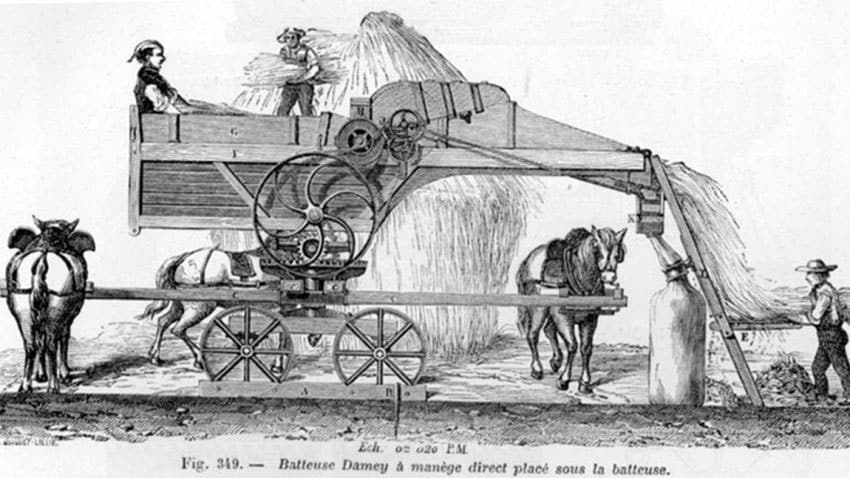

The Watt engine was a defining development of the Industrial Revolution because of its rapid incorporation into many industries. Boulton & Watt’s first customers came from the mines, but it was Boulton who saw the potential for other applications. Boulton encouraged Watt to convert the reciprocating motion of the piston to produce rotational power for grinding, weaving, and milling. Very quickly, paper, flour, cotton, and iron mills were all being powered by Watt’s engines. Boulton & Watt both retired in 1800 and handed over the business to their sons. Watt spent his remaining years carrying out further research and eventually died in 1819, to be buried, fittingly, alongside his loyal business partner, Matthew Boulton.

Watt was a true pioneer of industrial modernity and his brilliance lay in an innate ability to apply his theoretical knowledge of science in practical ways. Cornish chemist and inventor Humphry Davy said: “His inventions demonstrate his profound knowledge of those sciences, and that peculiar characteristic of genius, the union of them for practical application”.

Watt’s improvements to the steam engine breathed new life into industry by making efficient and reliable motive power available for the first time, while also leading to large-scale urbanization as rural families flocked to the towns and cities. After a historic first-hand account of the young Watt’s kettle experiment surfaced in 2002, Sotheby’s director James Miller said: “Were it not for James Watt, the Industrial Revolution might never have happened. He was not only the most prolific innovator imaginable, he also possessed one of the greatest minds of his time.”

… that James Watt came up with the concept of horsepower in 1783 to describe the power output of an engine. Having already adapted and marketed a steam engine for pumping water from underground mines, Watt was keen to introduce his “rotative” steam engine that he believed could outpace the horses used by brewery mills as the source of power. Despite his confidence in his engine’s potential to massively improve production rates, for marketing purposes, Watt knew he still had to convince the brewers by putting the steam engine’s specifications into a context they would understand: horsepower. Watt calculated that a horse was capable of lifting 150 pounds by almost 4 feet in one second (equivalent to 550 foot-pounds per second).

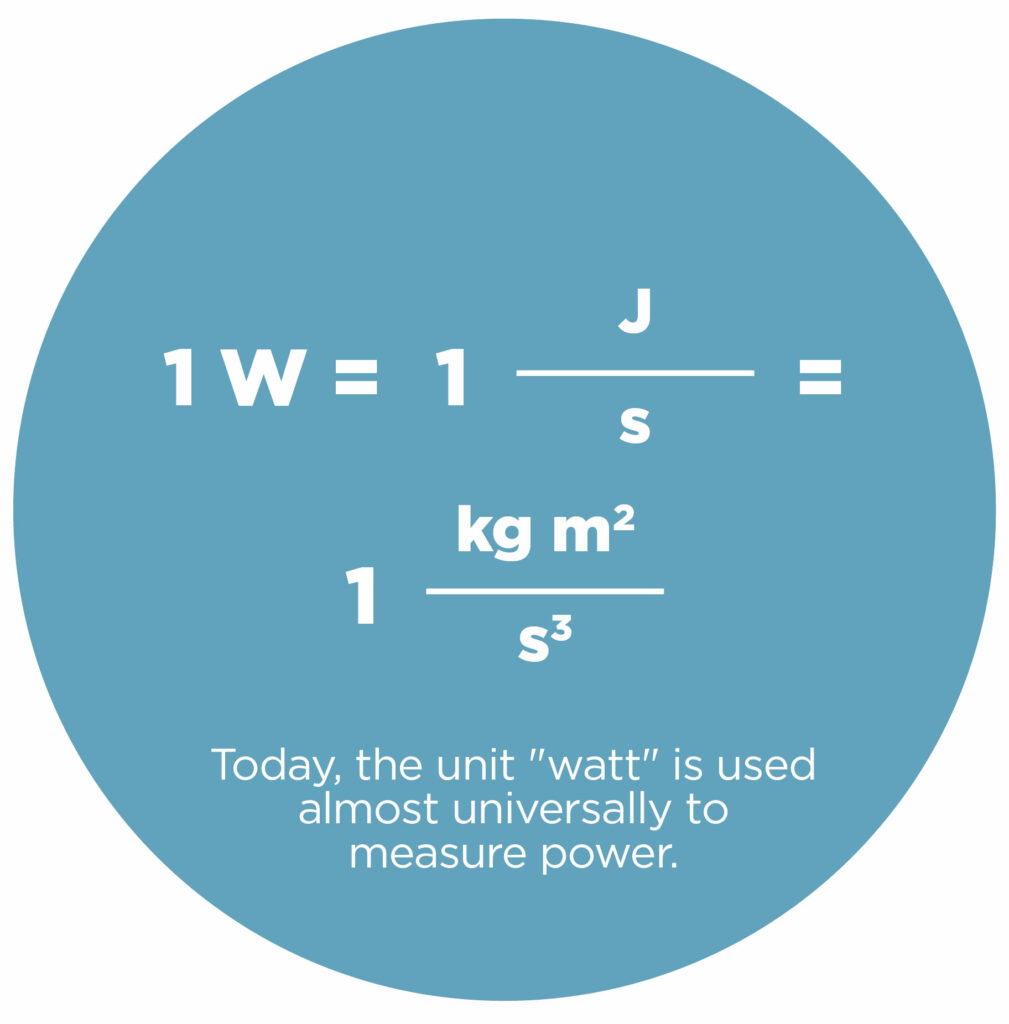

The SI unit of power, equivalent to one joule per second, corresponding to the power in an electric circuit in which the potential difference is one volt and the current one ampere.

The “watt” was recognized by the Second Congress of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1889. In 1960, the 11th General Conference on Weights and Measures adopted it for the measurement of power into the International System of Units (SI).

Timeline

1736

Watt is born in Greenock, Scotland.

1765

Watt invents the separate condenser.

1781

Watt invents the sun-and-planet gear.

1782

Watt patents the double-acting engine, where the piston both pushes and pulls.

1784

Watt invents the parallel motion: “One of the most ingenious, simple pieces of mechanism I have contrived.”

1785

Watt is elected fellow of the Royal Society of London.

1790

Watt invents the pressure guage.

1794

Approaching retirement, Watt founds the firm Boulton & Watt, which built the Soho Foundry to produce steam engines.

1806

Watt becomes an honorary doctor of laws of the University of Glasgow.

1819

Watt dies in Heathfield Hall, near Birmingham, England.